Textbook Reading Routine

By Sue, a Peer Tutor

I used to think that textbooks were useless: they typically have hundreds of pages, contents irrelevant to class, and unexplained pieces of information. Unlike lecture videos or study guides, textbooks are raw. They discuss too much information using abstract academic language. However, as I entered my sophomore year, I found textbooks to be irreplaceable as part of my preview routine before lectures since no other resources can organize content as clearly as textbooks do.

My attitude towards textbooks changed after I found the method that worked best for me. I benefit the most from reading textbooks when reading them before lectures. Since textbooks are content-rich, instead of reading them carefully at once, I read them roughly four times:

- 1st time: Big picture of the content

- 2nd time: Figures and boxed formulas

- 3rd time: Application of concepts learned, examples

- 4th time: Take notes – summarize things that looked important/interesting, record questions

After getting the specific information I want from the textbook before class, I find the lectures to be more enjoyable, where I can ask more relevant questions and have a better understanding of the material. Here are the specific steps I use for reading the textbook:

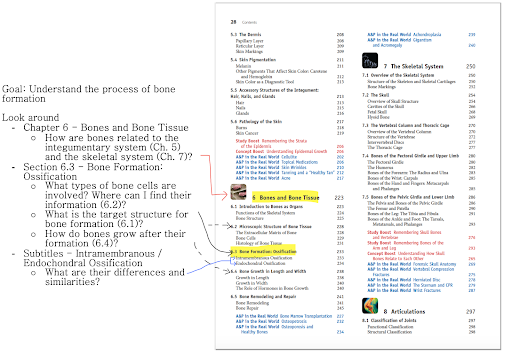

Getting the Big Picture

Before I start delving into the text, I need to first set up a goal—which topic do I want to learn more about? After locating the specific part of the textbook that I want to look at, I first glance over the titles of nearby chapters and sections to have a general understanding of the content. I am looking for the overall topic and the connections between chapters in this round of reading.

At the same time, I glance over the text and identify the bolded terms and their definitions. For the case above, I would take notice of the words “intramembranous ossification” and “endochondral ossification” (under the highlighted section “Bone formation: Ossification”).

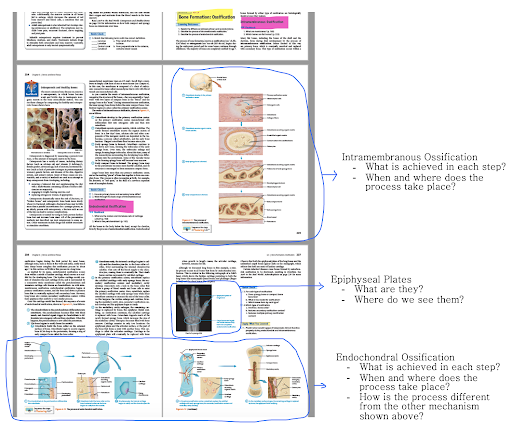

Figures and Boxed Formulas

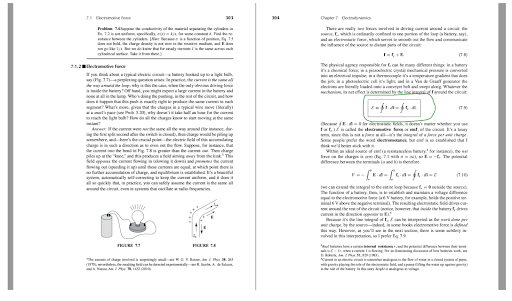

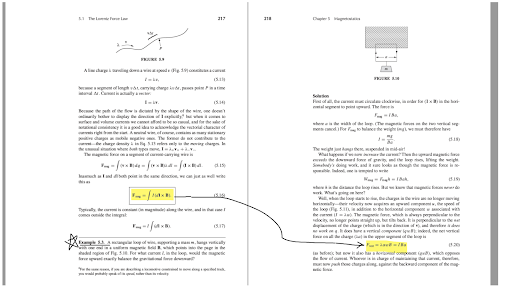

In this step, I focus on the most straightforward message from the book – figures and boxed formulas! As shown above, chemistry and biology textbooks usually contain many figures. The equivalent format in physics and math textbooks is boxed formulas. Similar to figures, I try to interpret the formula myself and search for variables and constants that I haven’t seen before through texts. I take special notice of how the formula is derived as well as the assumptions made in the process.

Application of Concepts Learned: Examples

After I have a general impression of the content, I look at example problems to see if my understanding is accurate. Before I look at the solution, I typically think about the problem for five minutes and record my thoughts on a scratch paper. Then, I compare what I wrote down with the solution provided.

Take Notes!

As the last step of my textbook reading routine, I summarize what I learned from steps 1-3. After grasping the general idea of the sections I read, I write down several bullet points to remind myself of what I went over. I also include questions I had in steps 1-3, and potentially I will learn the answers to them during the lecture, or I will ask my professors about them.

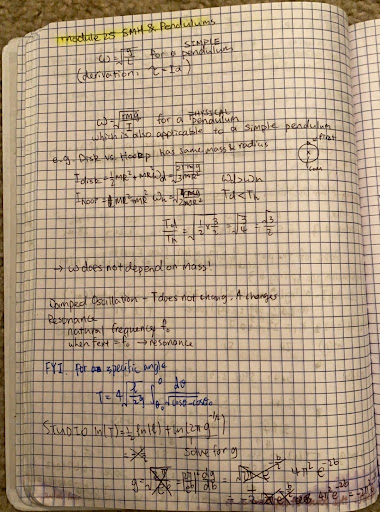

As you can see pictured below, when learning about the simple harmonic motion’s application on the pendula, I recorded the form of angular velocity as well as a hint on how it is derived (using torque and Newton’s second law), yet I didn’t include the whole derivation nor extensive words describing the equation.

After going through all four steps, I’m usually able to grasp the course content well. During the lecture, I can repeat and apply the knowledge. It seems that reading the same content four times is time-consuming, yet with clear goals in mind, each step takes 5 minutes or less, so I spend less time preparing for class in the end. My textbook reading habits also helped me with academic journal articles since both texts use abstract scientific language. As I look back, textbook reading separates my college studies from my high school experiences. Through textbooks, I learned to study independently—without professors feeding me chunks of processed knowledge. Besides being very prepared for class after doing my textbook readings, I saw my potential to learn and grow on my own. After every 20-minute session, I feel I became better at handling challenges.

(The learning center also incorporates handouts on textbook reading that you can check out!)

This blog showcases the perspectives of UNC Chapel Hill community members learning and writing online. If you want to talk to a Writing and Learning Center coach about implementing strategies described in the blog, make an appointment with a writing coach, a peer tutor, or an academic coach today. Have an idea for a blog post about how you are learning and writing remotely? Contact us here.