PowerPoint: More than Presentations

By a UNC Graduate Student

My brain already feels fried, and this is only my third paper of the semester. For my other writing assignments, I’ve always made an outline before I started writing. Outlines don’t always feel helpful, at least not for me. In any case, I’ve been trying to find a new method to jumpstart my writing. Imagine how surprised I was when I realized that PowerPoint–yes, PowerPoint–could be used for more than presentations. Dare I say, I’ve turned PowerPoint into a writing tool.

PowerPoint as an organizing tool

When I write a paper, I usually have to convince my readers of a particular argument or viewpoint. This means that, like all writers, I have to organize and present my information in a way that would be understandable to another person. One way to organize my thoughts is through an outline. But as I fiddled with a presentation for class, it dawned on me that, like an outline, PowerPoint has a linear structure. The slides appear sequentially, and I can put whatever information I like on each.

Would you like fries with that?

I should say upfront that I haven’t used this for one of my papers, not yet at least. So, for now, I’m going to imagine that I’m in a Food Studies course and have been asked to complete multiple tasks for a long paper. First, the assignment asks me to identify my favorite junk food (me? junk food? never…) and to trace its development over time. The prompt then asks me to consider several questions: When was this food first mentioned in historical documents? Are there regional variations? What do people call it in different times or in different places?

I do have a favorite junk food: French fries. I’ll even imagine that I’ve done my research and that I have a lot of information to answer these questions. Even so, I’m not sure about how to start organizing all my evidence.

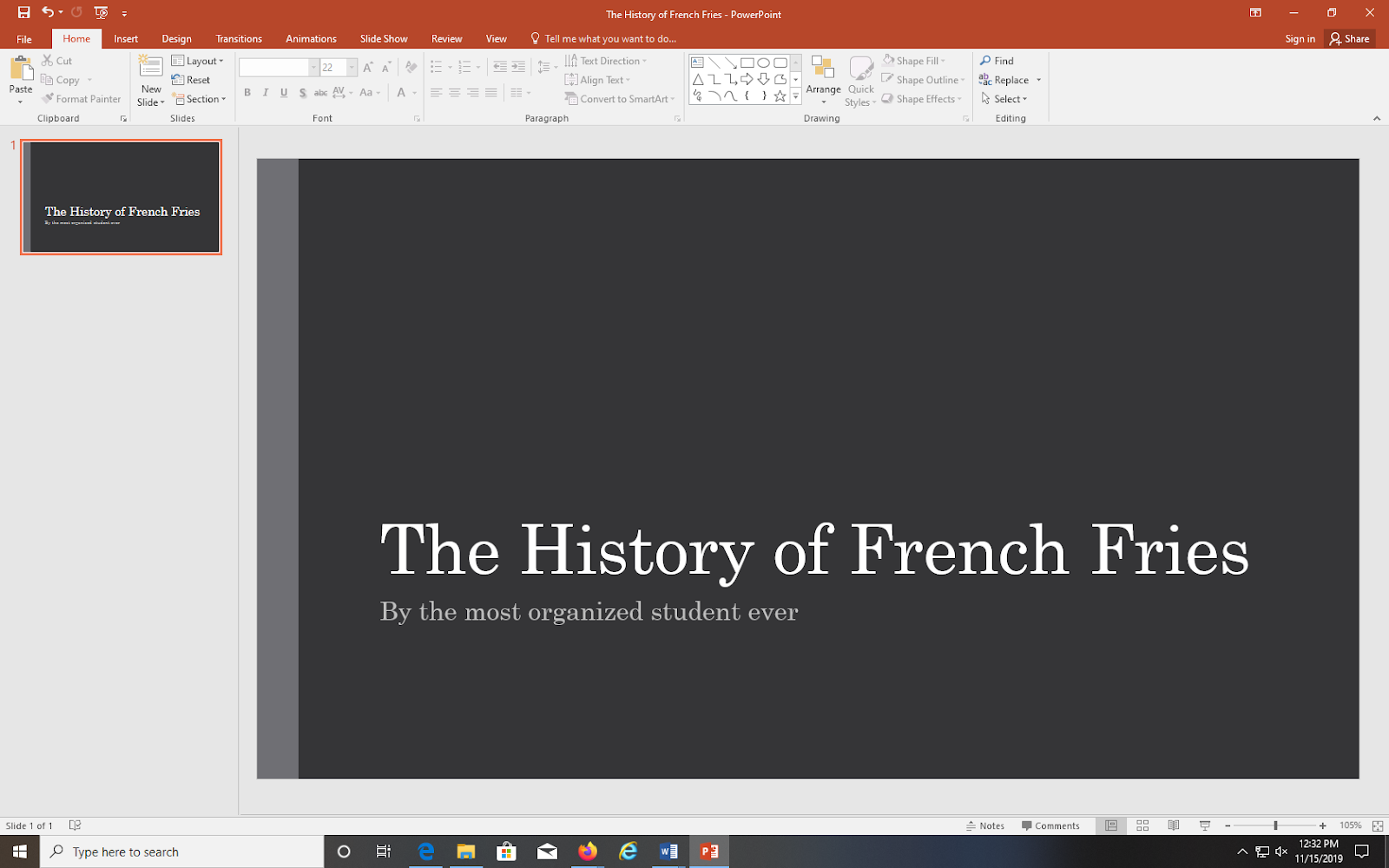

See the PowerPoint slide in the screenshot below. Here, I’ve given the document the same title that my future paper will possess: The History of French Fries.

Next, I make slides for each of the major points of evidence found that I plan to include in my discussion. At this point, I try to keep my sights on the big picture. I find that starting with a slide that answers possible questions from my audience (if I were presenting to real spectators) forces me to understand the most essential information about my topic. After all, this information might be crucial to include in an introductory paragraph!

PowerPoint: Not just for typed words

I may also decide to add an image or symbol connected to each topic.

For example, once I have most of my evidentiary slides up, pictures can help me group different points together. In the example below, I have several slides with flag symbols on them. These slides might be for the sections of my paper that discuss the different countries that claim to have invented French Fries, or they might consider the ways French fries are served in different countries. Images keep my creative side processing and keep me attentive!

Filling in more of my slides with details, as if I were presenting information to my classmates, helps me decide which information is important and which isn’t. When I’m stuck, I usually ask the following question: What kinds of bullet points would help my classmates to take great notes on this topic? The answer, more often than not, separates the important from the unimportant.

Each slide can become an individual paragraph. At this point, though, the paragraphs are disconnecting. There’s nothing explicitly connecting one paragraph to the next. I pause to think about the slide order, which prompts me to draft transitions between these paragraphs. How would I transition between slides during an oral presentation? If I decide that one topic might fit more easily at an earlier point in the paper, I move the slide up! Does it make sense in its new location? I won’t know for sure until I try it out.

Matching each slide with a particular topic or bit of evidence has also helped me see the layout of my argument. In some cases, I might even write out the main idea that I want to argue for each slide (either on the slide itself or the section for speaker’s notes at the bottom). These points can be recast into topic sentences when I start drafting the paper! The following slide contains a draft of one of these topic sentences.

Transferring the material beyond PowerPoint

Once I complete my slides, I have a working outline for my paper. Now I can begin writing a draft. After working through this process, I can say with confidence that my topic may be fried, but I’m not.

This blog showcases the perspectives of UNC Chapel Hill community members learning and writing online. If you want to talk to a Writing and Learning Center coach about implementing strategies described in the blog, make an appointment with a writing coach or an academic coach today. Have an idea for a blog post about how you are learning and writing remotely? Contact us here.