Papers as Puzzles

By a UNC Student

Imagine a friend of mine comes over to my house for a puzzle night, where we’re going to sit down and put together a jigsaw puzzle. Being a poor graduate student, I can’t afford a brand new puzzle, so I have a second-hand one. Unfortunately, there’s a problem: the puzzle isn’t in its original packaging, so we don’t have a picture to reference while we put it together. We’re going to have to start with just the pieces.

Where would we want to start? I assume we’d start with the edge pieces: we’d dig through the pile, find all the pieces with flat edges, and construct the border of the puzzle–the outline.

OK, fine. But what if our puzzle looked like this:

Uh, oh: no edge pieces. Now what? Stop and think about it for a second. How could we approach putting together a puzzle with no reference picture and no border?

I’d probably start by flipping all the pieces colored-side up, and then I’d make piles of the pieces with similar colors. This strategy would allow me to see what I’m working with. Which two red pieces fit together? Which two yellow pieces fit together? Which pieces contain two different colors and can serve as a bridge from one color to another? Piece by piece, I’d start to build a picture of the whole puzzle. Rather than starting with the big picture and working my way down to the individual elements, the usual strategy, I’d start with the little bits themselves.

Papers as puzzles

What do puzzles have to do with writing a literature review, lecture, or dissertation? Well, for me at least, quite a bit. If you’re writing a dissertation, you may not even be able to estimate within 100 pages how long your project will be when it’s done! Maybe you’re writing in a new genre, such as a policy brief, and you’re not sure what a finished policy brief looks like. Maybe you’re writing in a genre where the overall structure of the final product is something you learn along the way, as in a literature review or a lecture outline.

By applying these strategies to my writing process, I now think of my own writing as a puzzle. The techniques that I’d use during my puzzle night are also useful for making progress on writing, especially when the project’s structure won’t become clear until closer to the end. To illustrate how this works for me, let’s look at an example of a lecture series about Marx that I recently wrote.

Step 1: Research and brainstorm

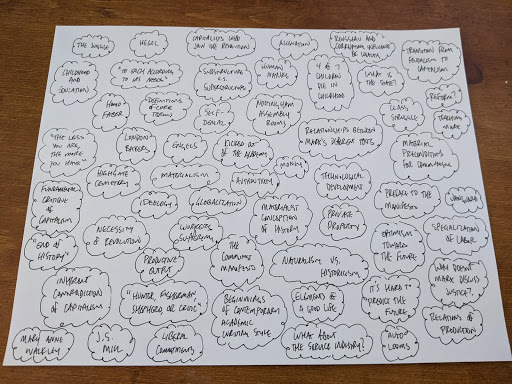

The first phase of my writing process is learning and thinking about the topic. This phase almost always involves some reading and note-taking, as well as fiddling with arguments in my head, thinking of examples, and considering issues from multiple points of view. While I’m working, I write the ideas down on a sheet of paper, surrounded by a little thought bubble, like so:

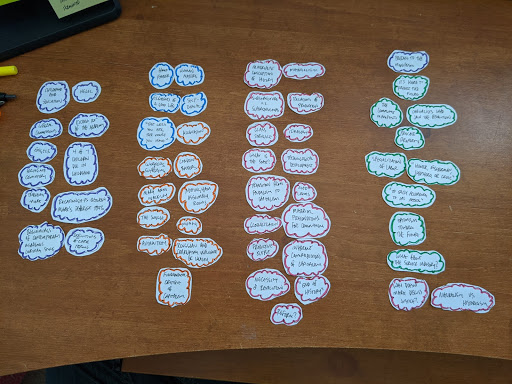

While I’m in the reading and brainstorming phase, it’s critical that I don’t worry about where my thought bubbles land on the page. I’ll rearrange them in a later step. For now, I try just to get everything onto the page, sort of like making sure all the puzzle pieces are dumped on the table. With so much information fluttering around in my head, scattered across multiple documents of notes, and scribbled onto sheets of scratch paper, consolidating them into one place is a real accomplishment. Details don’t matter yet. Each little bubble corresponds to a larger idea, the finer points of which are someplace else. When I finished collecting ideas about Marx, my paper looked like this:

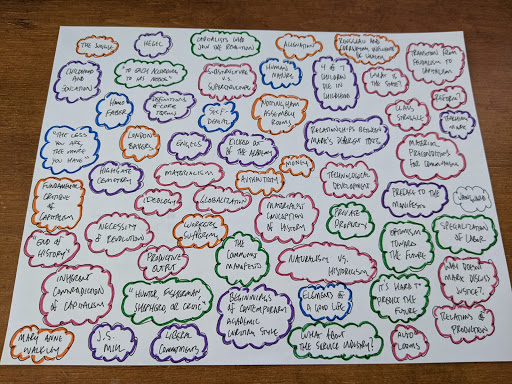

Step 2: Color-coding

The next step for putting together the puzzle was to collect the pieces that had similar colors, which happens to be the next step in my writing process. I sit back and look at the piece of paper. What general trends do I see? What major groups of ideas can I already start to discern? How many of those groups are there? For this stage, it’s important not to look too closely. After all, every idea is different (otherwise it wouldn’t have its own bubble!), so there’s a tendency (at least for me) to try to assign every idea its own color. Don’t do that. I try to identify no more than three to five big themes per sheet of ideas. Once I’ve chosen those themes, I grab some markers and write a legend for myself on the back of the paper.

After I’ve decided what colors to use and what they mean, I go through my thought bubbles one at a time, assigning them each a color. When color-coding, I resist the urge to assign one idea more than one color. If I can’t choose just one color to assign to an idea, it’s usually a good sign that my idea is too general. I break it down into smaller parts and color-code those instead.

If an idea doesn’t fit any of my colors, that’s OK! This result could mean lots of things: the idea could be extraneous, I could just be overlooking a connection to one of my themes, or the idea might live between the themes as a sort of transition or bridge. My strategy for those kinds of ideas is not to force it into a category. Instead, I leave it uncolored. In fact, I had one bubble like that for my Marx lectures, the idea of a vanguard.

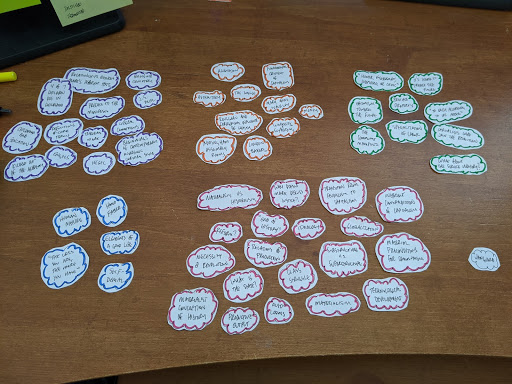

Step 3: Use scissors

Now that all of my puzzle pieces are face-up (to continue the analogy), it’s time to get them into piles with other pieces of the same color. My favorite method is to bust out a pair of scissors and cut the ideas out of the paper. For me, this step often goes pretty quickly. It took me about fifteen minutes to cut apart my Marx lecture notes.

It’s not strictly necessary to cut the ideas out of the paper. I’ve certainly tried other approaches. In the past, I’ve replicated all my idea bubbles onto another sheet, placing the like-colored ideas next to one another to organize them by major theme. I’ve also used the color-coding markers to draw lines between related ideas, which creates a concept map. I didn’t have enough space to draw lines on my Marx lecture notes, but I have used the line strategy in the past for some of my dissertation research.

Whatever strategy I use, the goal of Step 3 is to group like-colored ideas together so that I can start thinking about how these ideas relate to one another. When I was putting together the jigsaw puzzle, I was asking myself questions like, “Which two red pieces go together?” That’s a perfectly sensible question to ask myself about my Marx ideas: How do the blue ideas relate to one another? Which ideas are dependent upon others? Which ideas don’t require any other ideas to explain? Which of the ideas in my blue pile seem like the best segues to the next color?

I prefer to actually cut out the ideas so I can physically move them around as I work through these questions. At this stage, I don’t know how everything should be ordered. After all, the order is exactly what I’m trying to determine through this whole process! If I’m struggling to see how everything might fit together, sometimes a good first step is to arrange the ideas in any order. Once I’ve done that, I can see how it looks. Even though it’s sometimes hard to imagine in advance what the best order of ideas might be, it’s often pretty easy to spot bad orders. Again, writing is like a puzzle! I wouldn’t be able to tell whether two puzzle pieces definitely fit together or not until I try to put them together. With all the little thought bubbles cut out, I follow the same procedure for my ideas as I did for my puzzle pieces: try to smush them together to see what happens!

Step 4: Outline (finally!)

As I tinker with my piles of ideas, things start to click and make sense. Certain ideas, like pieces of a puzzle, “stick” to each other, and a recognizable order begins to emerge. The group of ideas as a whole begins to take on a form. That’s what I was after the whole time!

One thing I notice my lecture series outline is that some ideas no longer live with ideas of their same color. That’s fine by me–if they turn out to live more comfortably somewhere else, then I’ve learned something valuable by doing this exercise. Some colors also seem closer than others. For example, my blue and orange ideas seem directly related to one another, whereas the purple, pink, and green ideas seem to stand on their own. Thanks to that observation, I was able to easily see where to separate ideas into different lectures: purple, blue, and orange ideas became the first lecture, pink ideas became the second, and green ideas became the third. Lastly, sometimes ideas fall out altogether during this phase, like the one little bubble that I couldn’t decide how to color. All three of these outcomes offer valuable insight into the best way to organize the content of these lectures in a way that makes sense, flows easily, and remains on target.

When the shape of the final product begins to become apparent, I finally open a document and begin writing. Sometimes, I create an outline that reflects the current order of ideas. Other times, I leave my little pieces of paper on my desk (tape helps keep them in place) and start writing, using this outline instead of an electronic one. Regardless, by treating my writing as a puzzle and starting from individual ideas and working up, I now have a sense of what form the final project will have, which is what I lacked before I started. Armed with the knowledge about where I’m heading and how I’ll get there, I’m ready to get writing.

This blog showcases the perspectives of UNC Chapel Hill community members learning and writing online. If you want to talk to a Writing and Learning Center coach about implementing strategies described in the blog, make an appointment with a writing coach or an academic coach today. Have an idea for a blog post about how you are learning and writing remotely? Contact us here.